There’s no denying that Devin Addington is a fighter. The 15-year-old has been fighting since the day he was born, battling a number of health issues that landed him in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for the first nine weeks of his life. Then a heart transplant gave him and his family new hope.

There’s no denying that Devin Addington is a fighter. The 15-year-old has been fighting since the day he was born, battling a number of health issues that landed him in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for the first nine weeks of his life. Then a heart transplant gave him and his family new hope.

“It was a whirlwind,” said his mother, Nicole Derusha-Mackey. “Even looking back at it today, it was all so surreal.”

Devin struggled to breathe as soon as he was born, his mother said. He was rushed to the NICU, where an X-ray revealed dilated cardiomyopathy – the same condition that claimed the life of his younger brother, Nate, when he was just two weeks old. Devin was intubated and med-flighted from Grand Blanc to the University of Michigan, where he spent nine weeks in intensive care with complete heart failure. He went into full cardiac arrest when he was three weeks old, and it took doctors 10 minutes to revive him. He was relatively stable after that and, six weeks later, doctors had good news: A heart from a donor was available.

“It was like being at both ends of a roller coaster,” said Derusha-Mackey. “We knew it was the only way he’d ever be able to leave the hospital. There wasn’t a ton of fear; we mostly felt excitement and hope.”

The transplant procedure was a success, but Devin wasn’t out of the woods yet. He spent another month in the hospital recovering, fighting infections and learning how to eat. Doctors still did not know what caused his heart condition, to begin with, and it wasn’t until he was two years old that he was diagnosed with Barth syndrome, a rare life-threatening genetic disorder.

There is no current cure for Barth syndrome or effective treatment for the condition itself. Derusha-Mackey said the best they can do is manage and treat the symptoms, which include cardiomyopathy, an inability to fight infection, growth delay, and muscle weakness. Devin takes 17 medications and three supplements up to three times daily to manage his symptoms. Historically, those diagnosed with Barth syndrome succumb to heart disease or infections by the time they are three years old, however improved diagnosis and treatment have improved the survival rate. Derusha-Mackey also said she was told Devin would probably need a new heart before he hit his teenaged years.

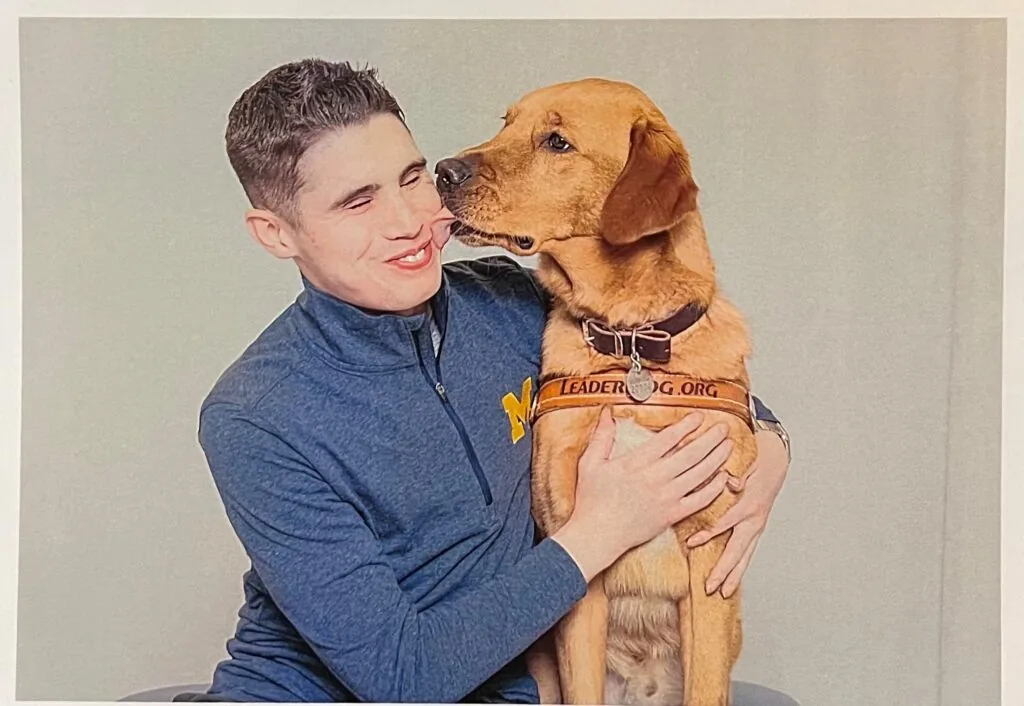

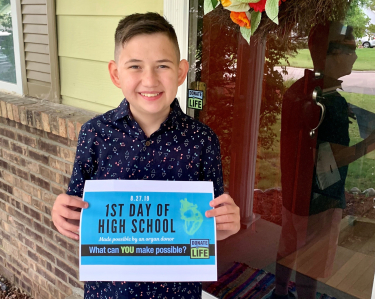

He has beaten those odds, although he struggles with muscle weakness and fatigue and is small for his age. He started his freshman year of high school this year and, in his free time, enjoys hockey and visiting zoos. He cannot play hockey but enjoys watching and is obsessed with the sport, his mother said.

“He continues to do well,” she said. “He’s a fighter.”

They have since met their donor family and schedule activities together around Sept. 21, which they refer to as Devin’s “new heart day.” Derusha-Mackey, who is a regional coordinator for U.S. Sen. Gary Peters, also advocates for people with Barth Syndrome, as well as Gift of Life Michigan to highlight the need for organ donors in Michigan.

“It’s like repaying the universe for this amazing gift we’ve been given,” she said. “I’m so grateful for the whole journey.”

One organ donor can save the lives of up to eight people and improve the lives of 75 others through cornea, eye and tissue donation. As of February 2020, there were 2,787 patients in Michigan awaiting life-saving organ transplants, including 129 waiting for a new heart. To sign up on the Michigan Organ Donor Registry, visit the Gift of Life Michigan website at www.golm.org.