‘I want to let everyone who struggles from all chronic diseases or illnesses know that there is a light at the end of the tunnel’

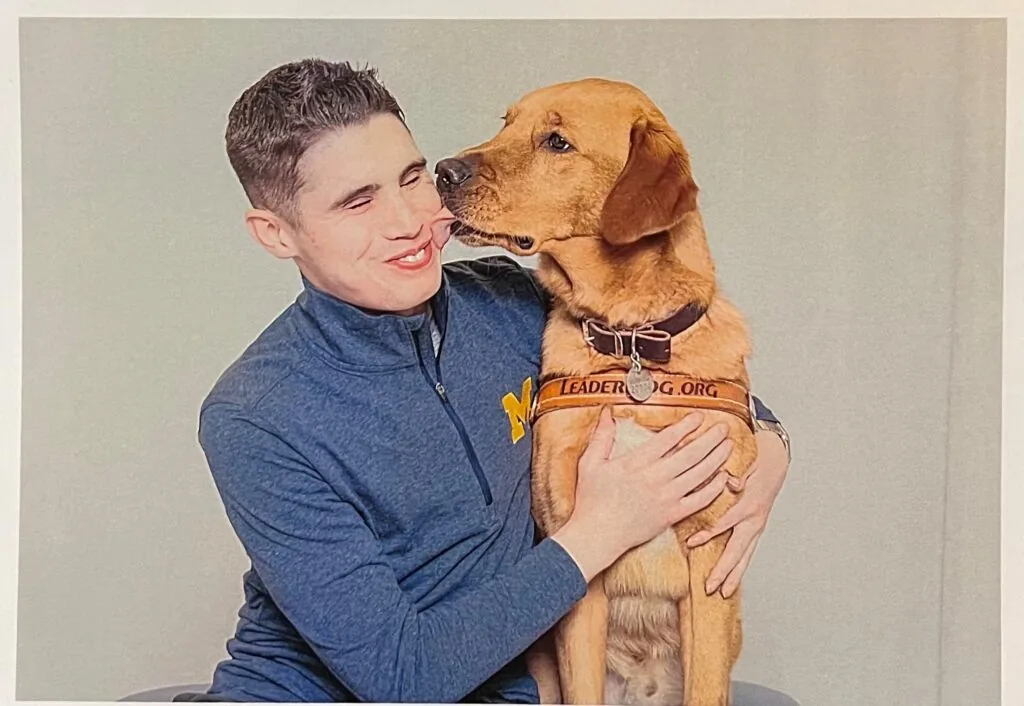

Mustafa Sharafi always wanted to be a father. Granted that wish more than two years ago, the 35-year-old Sterling Heights resident was just as grateful to celebrate this Father’s Day as he was last year, because doctors had told him he would not live long enough to realize his dream.

“To have a child is such a blessing. I never would have thought I’d be able to have a child,” he said. “Every time he’s with me, I don’t feel pain. I really don’t. he brings so much light and so much energy and so much love.”

Sharafi was born with a rare genetic condition called Tyrosinemia, a metabolic disorder in which the body cannot effectively break down the amino acid tyrosine. It typically leads to acute liver disease and is usually fatal; his older sister, Laura, died from the condition when she was only four years old. He was more fortunate: a matched liver donor was found and he received a transplant just 15 weeks after he was born – he was among the youngest liver transplant recipients at the time.

“I always tell people: I don’t celebrate one birthday, I celebrate two,” he said.

Even so, his prognosis was grim. His care team told him he most likely would not live past the age of 16, and they expected his life to be difficult. They did not think he’d ever grow taller than about four-and-a-half feet in height. He could not play any contact sports and had to take the extra precautions all transplant recipients must take due to their compromised immune systems.

More than three decades later, the 6’ 1” Sharafi has surpassed all expectations. He takes only a minimal dose of anti-rejection medicine but otherwise enjoys an active life. He gives credit to his care team, family and his faith.

“It is half my parents, half my physicians, nurses and medical staff – and all God,” he said.

He said he tries to be a living example of the good organ donation can do – a concept not necessarily embraced by the Arabic American culture. He hopes to change that. He volunteers with Gift of Life Michigan, providing education and talking with people who are hesitant to sign up or even discuss organ donation. Often, that is due to biases passed down from family members or friends or a lack of clarity in religious texts.

“People tend to use that as the number one excuse,” he said. “They’re more hesitant to sign up, or even listen about organ donation.”

It can be a difficult conversation, he said, but it’s a necessary one. Minorities tend to experience higher rates of conditions like diabetes, hypertension and heart disease, which can lead to organ failure. Combined with a reluctance to sign up as donors, it means that people from minority populations can spend more time waiting for a new organ than other patients. Of the more than 100,000 people on the national waiting list, nearly 60 percent are minorities. Sharafi said he wants to do what he can to change that.

“I want to let everyone who struggles from all chronic diseases or illnesses know that there is a light at the end of the tunnel,” he said. “We believe with time energy and patience others can be en route to healthy living and happiness.”

“With a lot of ethnicities and backgrounds, it depends on who you’re talking to and the demographic area,” he added. “I think it’s becoming more accepted; the younger generation is actually starting to understand and be able to say: that could be my family member, my loved one.”

Organ donation has, after all, helped him achieve his dream of being a father. He said he’s appreciative of every minute he spends with his 2-year-old son, Zain.

“He’s full of energy, full of excitement and he doesn’t give up, in terms of whatever he does,” Sharafi said. “That’s like me. I haven’t given up on anything I’ve done.”