Twenty years ago, Dr. Michael Hagan was living on borrowed time.

Hagan, 70, an Ann Arbor resident, knew he was ill, he just didn’t know how ill. He knew his liver was failing and his only hope for survival was a liver transplant. He had been living with that diagnosis — as well as the estimate that he only had 18 months to live — for about two years when he received the call that a donor liver was available.

“Gratitude is one of the main themes of my life. When I say I’m happy to be here; I’m really happy to be here,” said Hagan, who recently marked his 20th year post-transplant. “I’m actually happy to be anywhere. Every single day that I wake up, just the fact that I wake up, I say ‘Thank you, God.’”

A life in three parts

Hagan looks back on his life in three parts, each marred by tragedy but bolstered by hope. In the first, he was an emergency physician, a position he held for 10 years. When he became ill at the end of that decade, his doctors initially didn’t know what was wrong with him. Eventually blood tests sorted it out: he had contracted hepatitis B, most likely from a patient he had treated in the ER. His illness forced him to retire from that position, ending his “first life.”

“It was a very difficult thing for me,” he said. “I had trained my whole life for it.”

Eventually, he went back to school and earned a master’s degree in Health Administration. He went on to take a position of vice president of medical quality at a Metro Detroit hospital, but then tragedy struck again. His 20-year old son was killed in an automobile accident.

“He and I were very close; he was my only biological son,” Hagan said. “It triggered a relapse in my hepatitis, and I became very sick.”

That was when Hagan went back to his hepatologist at the University of Michigan and was told he had 18 months left to live. Once again, his illness cost him his job. He and his wife were also forced to downsize, to sell their home and move into a condominium.

“The bottom line is that within three months, I lost my son, I lost my health, I lost my job and I lost my house,” he said. “It was the worst time in my life.”

It was also the end of what he refers to as his “second life.”

Two years after that 18-month prognosis, he was worried. He knew from his symptoms that he was in full liver failure, yet he was still on the organ transplant waiting list. When the call finally came — four days before Christmas, in 1999 — he already had his bags packed. He and his wife rushed to the transplant center at U of M. The procedure was so successful Hagan said he woke up already feeling stronger. He also learned how close he had come: The liver is the largest organ in the body, weighing about four pounds, on average. His weighed four ounces. Doctors later told him he would’ve been dead in a week without a new one.

Hope, healing and advocacy

As he healed, Hagan couldn’t help but wonder about the person who donated the vital organ. All he knew was that the liver was from a 21-year-old, and it was healthy. He wrote a letter of appreciation to the donor family, but heard nothing back. Those correspondences are anonymous until both parties agree to exchange names or meet.

A series of coincidences pointed him to Shemika Rogers, a 21-year-old teaching student who had been murdered in Lansing. He looked into that tragedy and learned that the trial for Rogers’ alleged killers was about to start. Convinced that Shemika was indeed his donor, he drove 90 miles to the courthouse to watch the proceedings.

Hagan tried to remain anonymous, but the prosecuting attorney asked him why he was there every day. He told the man his story and outlined his believed connection to Rogers and then wrote a second letter for the prosecutor to give to the family, once the trial was over. Hagan was in the court hallway the day Rogers’ killers were sentenced, and he watched the prosecutor give the family the letter. They read it, looked up and Hagan said he saw recognition — and joy.

“When they realized who I was, 12 people came screaming down the hall. They gave me a big hug in front of the judge, the jury and everybody,” he said. “I don’t have words to express how we all felt that day.”

It was the start of his “third life.” Hagan got to know his donor family: They attended each others’ churches and told their stories. Hagan and his wife went to several Rogers’ family reunions, and vice-versa. Knowing him, he said, helped Shemika’s father and surviving children heal.

“I let them put their hands over my liver — their mother’s liver — and they realized that part of their mother is still alive and it has helped them with their grief,” he said. Shemika’s father, Jonas, told him that knowing part of his daughter was still alive helped alleviate the anger he felt toward her killers.

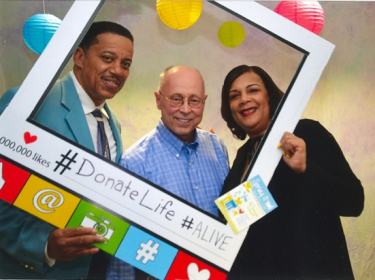

Hagan ultimately joined Gift of Life Michigan, where he has worked for 15 years and currently serves as chief quality officer. He has volunteered with Gift of Life since his transplant and continues to be a vocal advocate for expanding the Michigan Organ Donor Registry, frequently speaking to the critical shortage of available organs and tissue. He promised Jonas that he would tell their story in all 50 states and, just weeks ago, checked the final state off the list. He’s also spoken in 10 different countries and at high school diversity days, bringing home the message that we are all human beings and the color of our skin doesn’t matter.

Jonas Rogers said he still misses his daughter every day, but he’s appreciative of the work and advocacy that Hagen has done in the decades since receiving her liver. It’s brought him some peace, he said.

“It couldn’t have happened to a nicer person,” he said. “I have a lot of respect for Dr. Hagen and what he’s been able to accomplish.”

Since his transplant, Hagan has watched his children graduate high school, then college, then start their careers and get married. He’s seen six grandchildren born.

“I don’t feel like I got sick and got better; I was given a whole new life. Now I’m in my third life,” he said. “Without my transplant, I would’ve missed all of that. How precious is that? That is priceless.”