Mustafa Sharafi always wanted to be a father. He was granted that wish more than three years ago, when his son Zain was born, and said he has been grateful every day since.

“To have a child is such a blessing. I never would have thought I’d be able to have a child,” he said. “Every time he’s with me, I don’t feel pain. I really don’t. He brings so much light and so much energy and so much love.”

It’s even more incredible, Sharafi said, considering he nearly did not make it out of childhood, himself. He was born with a rare genetic condition called Tyrosinemia, a metabolic disorder in which the body cannot effectively break down the amino acid tyrosine. It typically leads to acute liver disease and is usually fatal; his older sister, Laura, died from the condition when she was only four years old.

He was more fortunate. He matched a generous donor and received a gifted liver when Sharafi was just 15 weeks old – he was among the youngest liver transplant recipients at the time.

“I always tell people: I don’t celebrate one birthday, I celebrate two,” he said.

Even so, his prognosis was grim. His care team told Sharafi’s parents that he most likely would not live past the age of 16, and they expected his life to be difficult. They did not think he’d ever grow taller than five feet tall. He could not play any contact sports and he had to take the extra precautions all transplant recipients must take due to their compromised immune systems.

More than three decades later, the 6’ 1” Sharafi has surpassed all expectations. He takes only a minimal dose of anti-rejection medicine but otherwise enjoys an active life. He gives credit to his care team, family and his faith.

“I’ve been very fortunate, very blessed. I passed all those boundaries,” he said. “It is half my parents, half my physicians, nurses and medical staff – and all God.”

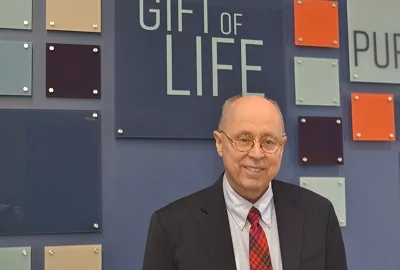

Sharafi tries to be a living example of the good organ donation can do – a concept not consistently embraced by the Arab American culture. He hopes to change that. He volunteers with Gift of Life Michigan, providing education and talking with people who are hesitant to sign up for – or even discuss – organ donation. Often, that is due to biases passed down from family members or friends or a lack of clarity in religious texts.

It can be a difficult conversation, he said, but it’s a necessary one. Multicultural communities tend to experience higher rates of conditions like diabetes, hypertension and heart disease, which can lead to organ failure. Combined with a reluctance to sign up as donors, it means that people from these populations can spend more time waiting for a new organ than other patients. Of the more than 100,000 people on the national waiting list, nearly 60 percent are from multicultural communities. Sharafi said he wants to do what he can to change that.

“I want to let everyone who struggles from any chronic disease or illness know that there is a light at the end of the tunnel,” he said. “I believe with time, energy, and patience others can be en route to healthy living and happiness.”

“With a lot of ethnicities and backgrounds, it depends on who you’re talking to and the demographic area,” he added. “I think donation is becoming more accepted; the younger generation is actually starting to understand and be able to say: that could be my family member, my loved one.”

Organ donation has, after all, helped Sharafi achieve his dream of being a father. He said he’s appreciative of every minute he spends with his son.

“He’s full of energy, full of excitement and he doesn’t give up, in terms of whatever he does,” Sharafi said. “That’s like me. I haven’t given up on anything I’ve done.”